Five years on from the Ash Cloud Crisis, what’s changed?

15 April 2015Today marks five years since Europe’s skies were plunged into an eerie quiet following the eruption of the Icelandic volcano, Eyjafjallajökull.

For eight days much of Europe’s airspace was empty of commercial flights following concerns that the volcanic ash would damage aircraft engines. It was the biggest air traffic shut down since the Second World War, with IATA estimating that it cost the airline industry £1.1 billion.

It was an unforgettable experience for everyone involved, and one that most people would probably never like to repeat. I was part of the NATS team that worked with the CAA, UK Met Office and DfT to develop a solution with the airlines and aircraft engine manufacturers that provided sufficient assurance for flights to operate safely.

These new procedures were developed in unprecedented time in order to get the skies moving again but while always ensuring that safety of the people flying was forefront in our discussions.

Last year when there were ominous rumblings detected from Bardarbunga, another Icelandic volcano, there was a lot of discussion about what would happen should another eruption take place.

For a start, we’d be very unlikely to see the same scale of disruption. Changes to safety regulations mean airlines can now fly at their own discretion and NATS would provide a service to any aircraft that needed it.

Initially, as in line with ICAO guidelines, a 120 nautical mile exclusion zone would be instigated around the eruption. The detailed process of understanding how severe the eruption was and the volume of ash expelled into the atmosphere would then begin.

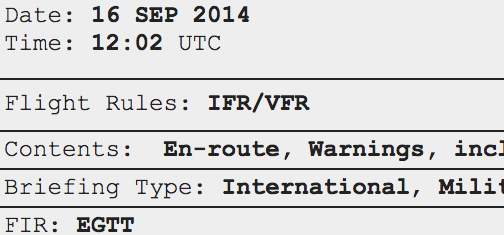

The UK Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC) – based at the UK Met Office – would then produce a forecast of the likely ash behaviour every six hours. That forecast would highlight the probable location of any ‘medium’ and ‘high’ levels of ash density.

Based on the VAAC forecast, the CAA would then issue a NOTAM advising airspace users of the location of those medium and high density areas. With that information and following procedures agreed with their own in-country safety regulator, airlines would then decide whether to fly and would issue their flight plans accordingly.

Eyjafjallajökull then and now. Photo taken by Systems Engineer Ben Swarbrick while visiting Iceland in March.

For those that do decide to operate, NATS would continue to provide an air traffic service as usual, routing aircraft around areas of ash much like we do during a thunderstorm.

In addition, a new capability has been established at a European level with the aim of aligning the actions of all parties in Europe with the ICAO guidance. The European Aviation Crisis Coordination Cell (EACCC) is comprised of senior advisors from across Industry and European institutions and would be established in order to ensure that State decision makers are given the right advice and information to protect the safety and efficiency of the fights operating within Europe.

The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull was an unprecedented event, but as you can see the industry learnt a huge amount. Next time will be very different.

What were your memories of the ash cloud?

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

15.04.2015

13:23

Simon Jackson

Given the stringent requirements with respect to safety assurance, did NATS ever document their justification for ‘re-opening’ the airspace when they did? Did they subsequently document this? It would be interesting to see how this was done and even more interesting to see how they measure the current argument, referred to above, in the context of their risk criteria and framework. Fascinating article by the way

16.04.2015

17:22

Robert

I found myself stuck on the Italian island of Sardinia although I have to admit I am sure that there are far worse places I could have found myself stranded. With no immediate prospect of a flight back to the UK and an urgent appointment to attend, I caught a ferry to Genoa and from there by train to Milan were upon I was fortunate to snap up two TGV tickets to Paris which had been returned to the ticket office. At Paris Gare du Nord station you had two options – either join an incredably lengthy queue to get tickets to the coast / UK or walk up to a self service ticket machine and get tickets in a matter of about 30 seconds or so. I did the latter. From Sardinia to London, it took me almost four days instead of the two hour flight !!

I actually wrote a case study on the effects of the volcanic ash cloud which has since been puiblished in the book “In Hindsight – a compendium of business continuity case studies”. While it takes in my own experience as an independent traveller, it also looks at the broader picture of the total disruption that businesses experiences suffered not to mention what effect it had on the Icelandic population too.

21.04.2015

15:55

Yannick

It provided further evidence of the importance of real time monitoring of volcanic ash to follow the trajectory of the plume. The use of satellite data is also undergoing further developments to improve the atmospheric dispersion model, NAME.