This week I spoke at The Journey Towards Autonomy in Civil Aerospace event organised by the Aerospace Technology Institute, addressing the challenges of fully automating ATM.

We tend to think of autonomous things as being about self-driving cars or machines doing things without any human input, but automation is something we are now becoming used to in our everyday lives. From our phones making suggestions for us, to our TVs automatically recording shows it knows we’ve watched before.

Automation for the aviation industry offers huge opportunities, and has the potential to open the skies to new airspace users and allow us to be more flexible and agile in the services we provide. It also poses some challenges, and there are three that I think will need to be considered above all others.

The first is safety. Safety for NATS is what we do, every second of every day. Our role is to safely move aircraft from one place to another as efficiently as we can. The safety of thousands of flights carrying hundreds of thousands of people every single day lies with us. To ensure that safety, layers upon layers of mechanisms and procedures are embedded into what we do.

Automation can bring with it the opportunity to further improve safety levels. And it’s already in our operation. The big jump for the future will be from controllers making the decisions with tools to support them. to the technology making the decision without a human to check and then ‘accept’ the solution.

A lot of time we compare the automation of the aviation industry with that of autonomous cars, but in reality, the safety levels within the two industries are not comparable. We need even more stringent acceptance criteria. Approximately 27,000 people are killed or seriously injured in car related accidents every year in the UK alone – that’s the same number of people it would take to fill 180 Airbus A320s. In 2019, there were approx. 257 commercial aviation fatalities anywhere in the world. The level of safety assurance that will be required to implement any automation will need to reflect that additional safety level.

This leads onto the second challenge: complexity. Airspace is complex and the way we manage it requires skill and judgement. It takes around three years to train as an air traffic controller, after a taxing selection process. The reason the human brain is so good at problem solving in this environment is because it can process a lot of information, but importantly, it can also deal with ambiguity. A machine can manage a lot more information, but not ambiguity. How do we ensure it can deal with a new scenario it has never seen before? How does a machine ensure the answer it creates is safe and efficient? It needs to be correct, 100% of the time.

Another complexity is our neighbours, we are working with European partners to harmonise air traffic management but if the UK had a fully autonomous ATM system, and our neighbouring ANSPs didn’t it would make the interface more than a bit tricky.

The third challenge is the human acceptance of automation – whether that’s the travelling passengers, pilots or regulators. If the human doesn’t trust the technology, then we may never see it reach its full potential. Acceptance by the passenger is important, but as we progress along the automation journey in the ATM environment, the trust between controllers and technology is essential, and that is why they are integral to the development of these technology and systems.

The hit of COVID-19 has really demonstrated the impact on the industry of external factors, and how we must remain adaptable and flexible. A technical solution today may be obsolete in a few years. But we know automation does and will play an increasing role in supporting our controllers in providing the safest and most efficient service to aircraft flying through our airspace.

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

07.08.2020

16:57

Jonathan Hammond

“It needs to be correct, 100% of the time.” Why?

Nothing complex will achieve 100%, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable, or that it can’t still improve on already excellent safety records. Would we claim 100% correctness today from air traffic controllers or pilots? Of course we have strength in depth, with various systems and process to provide cross-checks, as well as separation standards to provide safety margins for the rare occasions when issues arise. I don’t see any difference with increased automation of decision making.

I can well believe passengers will demand increased levels of safety performance from automation. I would too. But I think we do the public a disservice if we imply 100% correctness is necessary and/or achievable. In my view true acceptance can only be achieved with an understanding that risk is never zero.

13.08.2020

11:20

Isambert

Agree with the previous comment: 100% correctness for achieving complex tasks with machines is not the realistic target to set.

As result human will still be needed to take over the controls in such failure cases, with a smart and agile mind to analyse the traffic situation and make the right decisions.

21.02.2023

21:01

Henry Romberg

It needs to be as safe or safer than the current ATC system. Computers never get tired or make mistakes. Get the programming right, test the heck out of it and it’ll save lives.

25.03.2023

00:54

Ian

This article is really a red herring, planes are in an inherently spacious environment and the number of accidents reflects this. Cars operate and interact with other cars constantly, this is the reason for the differences in the death toll.

Air traffic control is inherently easy to automate however signalling has to change from a default of making radio calls to a digital system. Many accidents occur after misunderstood radio calls, poor separation management.

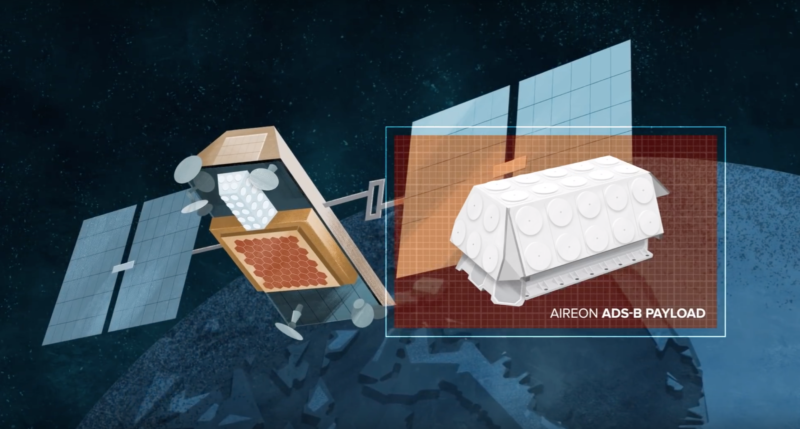

A simple review of ADS-B the “next generation” of air traffic technology reveals how backwards the current approach is, ADS-B as a standard is has no integrity controls so it’s possible to simply generation fake position signals, compared to a phone SIM which is uses PKI technology to stop impersonation this is an absolution failure of the standard process.

A digital standards should be the default where radio calls are simply replaces by digital messages, altitude, bearing, runway information and approvals should be transmitted in a textual format to stop misunderstanding. A fallback to voice based communications should only occur when the technology fails. This would lower pilot workload and stop current language barriers the terminology is difficult to understand for non-native speakers.