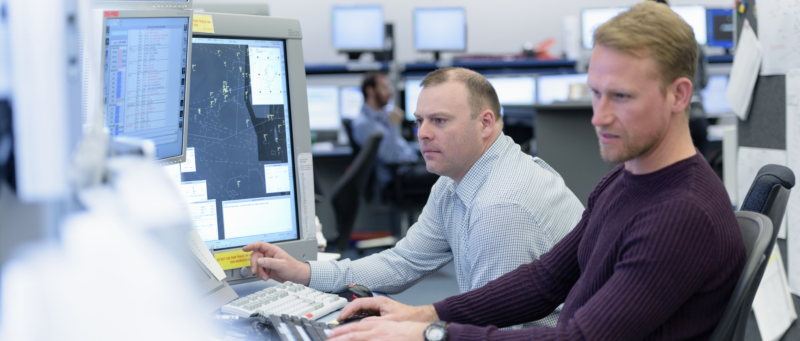

Mark Davenport, an air traffic controller at Swanwick centre looking after airspace around Gatwick, talks about his experience with airspace infringements for this week’s Infringement Series case study…

As an approach controller for over 25 years, plus a private pilot of considerable flying experience in the south of the UK, I am concerned about the number of infringements that appear to have been reported over the last year or so.

Although overall it would seem that the number of serious transgressions has not increased significantly, the number of infringements seem to have increased and I believe the consequences of this may not always be fully understood by the pilots that fly adjacent to controlled airspace.

“the consequences may not be fully understood by the pilots”

I can really empathise with my recreational flying colleagues. Although I only have about 200hrs of light aircraft experience I have 2500hrs gliding experience – a high percentage of which is flying 150-700km cross-country in England and Wales.

On many occasions during these flights I have had to conscientiously plan to fly around, or request clearance through restricted controlled airspace. It’s tough but it helps preserve our flying freedoms.

And I know most members of the general aviation community feel exactly the same way, so it is especially frustrating for me at work to be faced with pilots making basic navigational mistakes and leaving the controllers to ‘clear up the mess’.

“It is especially frustrating for me at work to be faced with pilots making basic navigational mistakes and leaving the controllers to ‘clear up the mess’”

The problem with infringements is that often, by definition, they occur very close to major airports…and the airport is almost always generating traffic that will be affected by them.

Whenever an aircraft infringes controlled airspace around the London TMA the controller gets an alert. If an alert occurs on the more peripheral parts of controlled airspace, or when there are few or no other aircraft nearby, then controllers can opt to take a view as to whether to take any action or not.

If the offending aircraft quickly leaves controlled airspace then often a phone call to the unit may be all that is required to get assurance that the situation is resolved.

“The problem with infringements is that often they occur very close to major airports”

One of the biggest problems is the knock-on effect on sector safety and efficiency. You have to prioritise resolving the risk created by the infringement and this inevitably reduces the effectiveness of the other routine ‘safety barriers’ – good readback listening, unambiguous coordinations etc.

When an infringement occurs, the controller is very often required to give avoiding action and traffic information. This also requires them to write a report as soon as possible after the event.

“One of the biggest problems with infringements is the knock-on effect on sector safety and efficiency.”

As a controller cannot be on a normal break whilst writing a report, this has a knock-on effect. Not only does it increase the workload of the controller involved, it also affects staffing levels on that sector and adjoining sectors as the supervisors try to staff the sectors following the unexpected admin work.

This becomes even worse if the infringement results in a loss of separation. The supervisor is then required to relieve the controller and carry out an initial investigation to ensure the controller has followed correct procedure.

I remember a particular pop-up infringement 10 nautical miles East of Gatwick when an aircraft climbed into the area I was controlling. There was nothing I could do to avoid losing separation as the infringing aircraft had climbed up within a mile of one of my aircraft.

Although no blame was attached to my subsequent actions, a full investigation ensued with all the scrutiny and emotional stress that inevitably involves.

“There was nothing I could do to avoid losing separation”

My advice to pilots is straightforward… if you suddenly become aware that you may be lost and potentially infringing, please call ATC, use your transponder and consider taking up an orbit to give yourself time to re-orientate yourself.

According to the Civil Aviation Authority, in 2018 there were a total of 1,358 reported airspace infringements. Analysis from previous years shows that:

- The correct use of a moving map with alert could have prevented 85% of infringements

- Using a frequency monitoring code (Listening Squawk) could have prevented 65% of infringements

- Recognition of/dealing with overload, fixation and distraction – possibly effective in 43% of cases

- Better familiarity with aircraft and equipment – possibly effective in 24% of cases

Pilots are encouraged to request entry into controlled airspace as early as possible, either by free call, radio transmission or our Airspace Users Portal.

Via the portal, https://aup.nats.aero/, pilots can submit a CAS request before their intended crossing so our controllers can prepare for their arrival – helping pilots with their requests and enabling safer use of the airspace.

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

20.05.2019

18:45

Matthew

Another good insight.