Easter traditionally marks the start of the busy summer season for the UK aviation industry. It usually coincides with the airlines’ switch from winter to summer schedules and heralds the school holidays over Easter, the Spring bank holiday and of course the long summer holiday. Not this year, though.

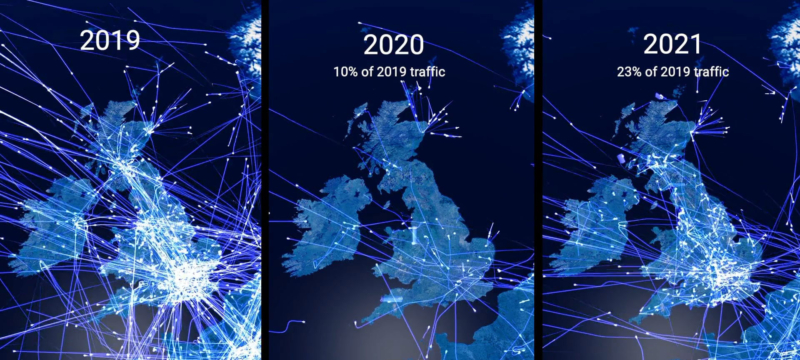

Our latest data visualisation is a really stark illustration of how hard the industry has been hit by the pandemic. We now have three Good Fridays to compare. This year traffic was at 23% of 2019 levels compared with virtually nothing last year, but that figure isn’t the full story. It doesn’t show up the fact that much of that traffic was overflights of the UK, while European traffic is down to around 13% of 2019 levels. Nor does it highlight the fact that a lot of these movements were local ones – private flyers, who were allowed to take to the skies again from March 29, and who took full advantage of the fabulous Bank Holiday weather. Finally, most flights at the moment are cargo with far fewer passengers flying than would ordinarily be the case even with 20% of traffic.

By Easter Monday the traffic level was down to 18% of 2019, and this is consistent with the overall average which has been bumping along at around 20% since Christmas. And with the Government still considering its “traffic lights” system, the much-needed summer on which the industry has been pinning its hopes is starting to look more uncertain and ever further away.

We echo the calls today by Heathrow’s CEO, John Holland-Kaye, for clarity on the traffic light system, for time to plan and prepare, and for the Government to make sure enough resource is available to support the restart. He makes the point that six hour queues in immigration are nothing compared to what they will be as traffic scales up, unless the Border Force systems and manpower are similarly scaled up. But consider for a moment what could happen if those queues do get even longer than they are today.

Once the arrivals halls are full, passengers will have to be held on the aircraft. Before long the stands, and then the remote stands will be full and airports may be unable to take more arrivals. That means aircraft being held on the ground at their departure point or, if they’re already on their way, being put into airborne holding patterns or even diverted. The environmental cost of that additional flying time will be considerable.

It’s interesting that Australia and New Zealand have already decided to open a corridor between them without testing and the US will not be testing on domestic routes. In the UK we are still waiting for clarity on the criteria for the traffic light system and the testing regime. When I look at the Covid position elsewhere in Europe, I can’t help wondering whether we will have a European summer. It feels more likely that we will have a US and Caribbean summer, given the similarities between our Covid incidence and our vaccination roll-out. But the truth is that we still don’t know, and the longer it takes for the Government to establish what it will do, the less time it leaves for the industry to prepare, and the more consumer confidence erodes.

Our refresher training for air traffic controllers is continuing through to the end of May and I’m as confident as I can be that we’re ready if and when we get the green light for international travel. But we are still playing a waiting game – the industry and the public desperately need clarity if we are to save the summer.

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

16.04.2021

09:17

Paul Hodge

Long may it continue being low flight numbers until aviation sorts out its devastating CO2 output.