The use of the phonetic spelling alphabet – Alfa, Bravo, Charlie etc – is a common sound in air traffic control towers and centres around the world, but where did it come from and why does everyone use the same one?

Letters like M and N and F and S can sound very similar, especially over the radio, so the phonetic spelling alphabet serves a vital purpose; helping ensure the messages that pass between air traffic controllers and pilots (as well as a host of other professions) are as clear as possible.

In fact, every air traffic control interaction is based on a standardised set of phrases designed to keep messages unambiguous – especially for anyone for whom English is not their first language – and the phonetic spelling alphabet is an important part of that.

The phonetic alphabet we use today – which is officially called the ICAO Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet, or NATO phonetic alphabet – was developed after the Second World War to try and bring about a level of standardisation, but it wasn’t the first.

The need for a spelling alphabet first emerged with the rise of radio telephony in the early 20th Century. During the First World War, the combination of battlefield conditions and embryonic radio technology meant messages could too easily be garbled and misunderstood. Both the British Army and Royal Navy developed their own spelling alphabets to combat the problem, with the Navy preferring a mix of Apples, Butter and Pudding over Ack, Beer and Pip for the Tommies in the trenches.

As civil aviation emerged in the early 1920s, an amalgamated version of these alphabets was rolled out by the UK Government for use by pilots and ‘Civil Aviation Traffic Officers’, including Zebra, Monkey, Uncle and George. But as global air travel grew, the need for a level of standardisation became increasingly paramount.

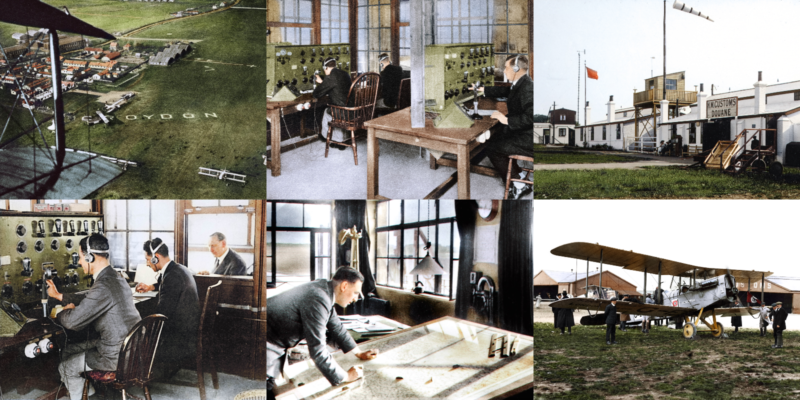

In 1932, ICAN – the International Commission for Air Navigation and precursor to ICAO – introduced the first attempt at an international spelling alphabet for civil aviation. Based almost entirely on city names – from Amsterdam to Jerusalem via New York, Oslo and Tripoli – it’s the version you can hear in this imagined MAYDAY call made by a stricken pilot to controllers at Croydon Airport.

The thing that is most striking about this version is just what a mouthful it is. It’s hard to imagine it being used in a real-life emergency and perhaps because of that, confusion continued with different iterations being in use around the world, not least an entirely separate alphabet in South America.

The need for the Allied powers to communicate during joint operations in the Second World War saw the US, UK and Australia adopt what’s commonly known as the Able Baker alphabet (having worked through versions that included Nan, Nancy and Norma). Able Baker was then adopted by civil aviation but was still found to be inadequate given how many words were unique to the English language.

So in 1948 ICAO began collaborating with Jean-Paul Vinay, a linguistics professor at the Université de Montréal, to create a new spelling alphabet that could be internationally adopted following vigorous research and scientific testing. This new alphabet needed to follow three golden rules:

-

-

- Each word must be ‘live’ and with similar spelling in English, French, and Spanish

- It had to be easily pronounced and clear over the radio

- None of the words could have a negative meaning or connotation

-

The key in choosing each word was the likelihood of it being understood in the context of others. For example, ‘football’ has a higher chance of being understood than foxtrot in isolation, but foxtrot was proved to be a better choice in extended communication. To change one word would therefore involve reconsideration of the whole alphabet to ensure that a change proposed to clear up one confusion did not itself introduce others.

The final choice of words was made after hundreds of thousands of comprehension tests involving 31 nationalities. The revised alphabet was then adopted on 1 November 1951 and came into use for civil aviation on 1 April 1952, although the words representing the letters C, M, N, U and X were later replaced with the Charlie, Mike, November, Uniform, X-ray that we’re so familiar with today.

That final version entered use on 1 March 1956 and has helped pilots, air traffic controllers and a whole host of other professions be clearly understood ever since.

Find out more about the history of air traffic control at nats.aero/atc100

Delta Yankee Kilo?

-

- eXtra was dropped in 1956 which was the only word that didn’t begin with the letter it represented

- Alfa is always spelled like this to avoid confusion over the ‘ph’ for non-English speakers

- Delta is replaced by Dixie at Atlanta Airport, where Delta Airlines are based

- Juliett is always spelled like this to make it obvious to French speakers that it’s a hard ‘t’ sound at the end, rather than silent

- Lima is replaced by ‘London’ in some areas, such as Malaysia, where ‘Lima’ means ‘five

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

03.04.2020

10:14

Bernard Dowley

Having instructed radio voice procedures for many years in both military and civil I found this most interesting and informative.

11.04.2020

11:07

Ronnie Brooks

Yawn.

27.05.2020

22:30

Joao Rodrigues ATCO

Good work memory of facts are important

many thanks

28.05.2020

10:55

Roy Booth

Great article Adam. It makes me cringe when I hear people on the phone making up their own phoenetic alphabet.

28.05.2020

11:26

Maria Gill-Williams

Really interesting – thank you.

02.06.2020

20:35

Martin James Howe

Thank you!

13.02.2021

23:05

Marilyn

Excellent. I found this very informative. Thank you.