While the technical advances made during the Second World War in areas such as radar and radio navigation provided the tools necessary for post-war civil aviation, the operating procedures and practices to efficiently and safely utilise those tools were developed a few years later.

On 24 June 1948, ground access to the French, British and American zones of Berlin was cut off by the Soviet forces in East Germany. On 26 June, the first airlift flights departed for West Berlin. Over the following fourteen months (ground access was restored by the Soviets in May 1949, but airlift flights continued until September 1949), over two million people were supplied with food, medicine, clothing, fuel, water and any other necessities by air.

By the end of the Berlin Airlift, nearly 300,000 flights by transport aircraft had supplied 2,300,000 tons of supplies in what was an incredible feat of planning, logistics and execution.

At the start of the crisis, Berlin had two operational airports; Templehof and Gatow. In July, less than a month into the resupply effort, it was acknowledged that airport capacity was a limiting factor and ground was broken for the construction of Tegel Airport on 5 August. It was operational only three months later in November 1948.

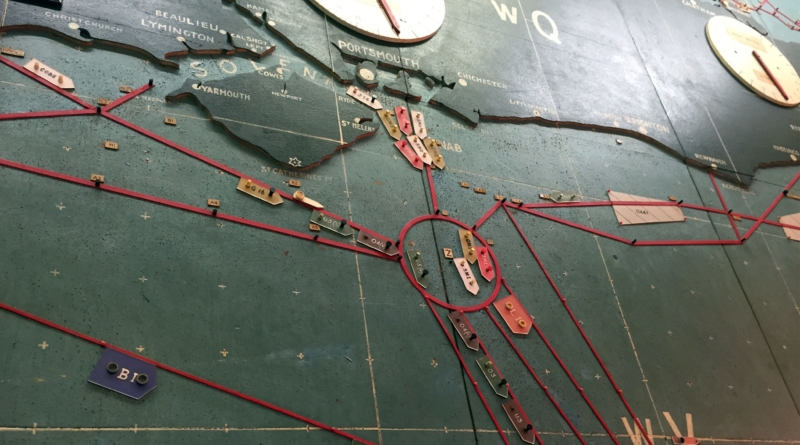

British and American officers consult a 3D map of Berlin airspace, with lengths of string tied between wooden pegs representing the vertically separated flightpaths (Picture IWM)

An incident six weeks into the airlift highlighted the requirement for standardised operating procedures for such a complex operation.

On 13 August 1948, a day that was to be known as ‘Black Friday’ among the transport crews, American Lieut. Gen. William Tunner, who commanded the airlift operation, was flying to Berlin in order to award a medal to an American transport pilot.

Weather was poor. The cloud based was only a few hundred feet, and heavy rain was obscuring the radars used to assist arriving aircraft. At Templehof, a Douglas C-54 transport had crashed on landing and was burning at the end of the active runway. The next arriving aircraft landed and blew its tyres in order to stop before hitting the wreckage. The one after that then swerved off the runway.

Arrivals were then halted, and aircraft began holding in the cloud, in a stack above the airport, including the aircraft carrying General Tunner. After a few minutes, Tunner called the control tower to instruct all aircraft to fly back to West Germany without landing (apart from his!).

Flight procedures for transport operations in the Berlin area, showing the complexity of the airspace. (Picture US DoD)

From that day onward, staff in the control towers at the two airports were instructed to be more proactive in terms of ensuring runway safety. Pilots were told to follow the direction of the controllers, and if any aircraft couldn’t land on its first attempt, it was to return to West Germany without attempting to land again.

Each runway would have a published standard missed approach procedure that every aircraft would fly, enabling the arrival and departure routes to be deconflicted, and mitigating the possible safety issues brought about by trying to fit an aircraft back into the sequence. All aircraft would be required to fly detailed, published routes, flying on instruments even in good weather, maintaining certain altitudes and adhering to speed constraints to ensure separation between aircraft. This policy, and the publication of such flight procedures in the Combined Airlift Task Force Manual (CATFM) to be followed by all aircraft, regardless of nationality and type, led to a dramatic reduction in accidents.

Today, each nation around the world publishes similar information in the Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), so any pilot can brief on the flight procedures in force anywhere in the world, and these documents can trace their origins back to the CATFM.

RAF ground crew being trained in aircraft positioning, in order to optimise turnaround times, using a model of RAF Gatow. (picture IWM)

The Berlin Airlift also saw the development of what would later come to be called ‘flow control’, a familiar concept in contemporary air traffic management. Each airlift base in West Germany was given a time period where its aircraft had to be flying over the radio navigation beacon at the beginning of the corridor on the inner German border. Each aircraft was specifically given a ‘slot time’, within thirty seconds of which it had to aim to be overhead the beacon. Between each slot time there was a buffer of three minutes, and between each base’s time period there was a buffer of six minutes. The three-minute arrival interval allowed one arrival to land, turn off the runway, a departure to then line up and take off, and for the following arrival, three minutes after the first, to have a clear runway just it was approaching the airport. The aircraft flew at certain altitudes according to which base they departed in West Germany; for example, flights from Lubeck were allocated 5500ft, and those from Wunstorf 3500ft.

Standardised instrument flight procedures, to be flown regardless of the weather, and published in one document and available to all flight crew and controllers, and a flow control system that is still recognisable today; both were born out of necessity, when a city struggling to recover from a war was kept alive solely by air, 75 years ago.

Comments

Please respect our commenting policy and guidelines when posting on this website.

03.09.2019

01:03

Glen Towler

Great stuff Adam. I hope our friends RH and AG read this.

06.09.2019

09:44

Johnathan Webster

Fascinating stuff Adam, thanks.

23.10.2020

09:54

Roger Knowles

Great stuff, my late father was an air traffic controller through the airlift, first at Gatow, then Tempelhof.

15.03.2022

12:00

Les Wood

Can anyone provide information about the staffing and functions of staff of ATC at Gatow in the Airlift?